In September of 2009, while living in the Netherlands, I was fortunate to visit Piet Oudolf’s nursery in Hummelo twice, which was located not too far from DeWiersse. I was able to visit once with Laura, from DeWiersse, and the second time with my good friend Tom Coward, head gardener at Gravetye Manor. It is a pity when you visit nurseries in other countries, seeing so many plants you wish you could have but, alas, cannot travel with or bring back. I am pleased to have in my possession the beautiful and informative purple nursery catalog, which has continued to be an excellent source of information for me. The catalog has been a great key for identifying many of the plants he continues to use in his gardens throughout the different countries I have seen them – Holland, England, and U.S., especially in my hometown of NYC at the High Line. Every time I move, I make sure this catalog is with me. In 2014, I saw Piet Oudolf speak about the plantings at the High Line in the Garden History Museum in London. I was able to have coffee with him after the lecture (due to the wonderful Stephen Crisp) and Anja Oudolf, his wonderful wife, was insistent upon letting people know that the nursery was now closed. The decision seems appropriate since there is more than enough international projects to keep them busy. With Eric’s beautifully descriptive explanation of the new book Oudolf Hummelo, I felt I had to share these images of a striking garden since I have never had the opportunity before. I have not labeled the images, for it is merely to enjoy, but if you are curious to know a combination, leave a note in the comments section below. – James

In September of 2009, while living in the Netherlands, I was fortunate to visit Piet Oudolf’s nursery in Hummelo twice, which was located not too far from DeWiersse. I was able to visit once with Laura, from DeWiersse, and the second time with my good friend Tom Coward, head gardener at Gravetye Manor. It is a pity when you visit nurseries in other countries, seeing so many plants you wish you could have but, alas, cannot travel with or bring back. I am pleased to have in my possession the beautiful and informative purple nursery catalog, which has continued to be an excellent source of information for me. The catalog has been a great key for identifying many of the plants he continues to use in his gardens throughout the different countries I have seen them – Holland, England, and U.S., especially in my hometown of NYC at the High Line. Every time I move, I make sure this catalog is with me. In 2014, I saw Piet Oudolf speak about the plantings at the High Line in the Garden History Museum in London. I was able to have coffee with him after the lecture (due to the wonderful Stephen Crisp) and Anja Oudolf, his wonderful wife, was insistent upon letting people know that the nursery was now closed. The decision seems appropriate since there is more than enough international projects to keep them busy. With Eric’s beautifully descriptive explanation of the new book Oudolf Hummelo, I felt I had to share these images of a striking garden since I have never had the opportunity before. I have not labeled the images, for it is merely to enjoy, but if you are curious to know a combination, leave a note in the comments section below. – James

Tag: Piet Oudolf

Plantsman Corner: Salvias of Slovakia

Seeing garden plants in the wild is always a pleasant, if not eye opening, experience. Familiarity is heartwarming, but one can also learn much from observing the immediate environment in which plants grow before tailoring our gardens to suit them once we return home.

I spent this past summer in Slovakia, a mountainous country situated in the hearth of Eastern Europe. It is a place of great biodiversity, and I enjoyed admiring the flora and botanizing. Although a wide array of plants is well represented, it is the wild sages (Salvia) that largely impressed me. They are ubiquitous and widespread throughout the country. Owing to their resilience and adaptability in disturbed habitats, salvias have an advantage over other species in the agrarian landscape here.

The first Salvia I encountered was Salvia nemorosa. It is common in central and southern Slovakia, growing in meadows and disturbed areas. Salvia nemorosa seems to love roadsides and a trail of purple often accompanied me on my peregrinations down to Austria or Hungary. Its flowering is a long affair, and even if it had been in bloom for some time since my arrival in early July, the flowers are still going strong as I pen these words at the end of August. The color is consistently a dark magenta-purple in the wild, although considerable variability appears in cultivation. Numerous cultivars have been selected for size and color, ranging from the diminutive blue ‘Marcus, scarcely a foot tall, to the tall pink ‘Amethyst’, towering over 3 feet.

Another cultivar worth mentioning here, but rather rare in North America is ‘Pusztaflamme’, an aberrant mutation with branched spikes of flowers that form a cone-shaped head. One presumes it must have been found in a meadow in Hungary since puszta, (pronounced ‘pussta’), is the Hungarian word for prairie. ‘Pusztaflamme’ is also known as ‘Plumosa’, a name that describes well the chenille-like texture of the flowers.

Although any Salvia nemorosa is deserving of a place in the garden, some sort are more dramatic than others. ‘Caradonna’, bred by Beate Zillmer of Zillmer Pflanzen in Uchte, Germany, is perhaps the most famous for its narrow spikes of dark purple flowers on black stems, an intense, but luminous combination.

Another common Salvia in Slovakia is a superb garden plant that I grow with fondness and ease in Canada: Salvia verticillata. This plant seems to prefer ditches, vacant lots and meadows where I saw it bursting with surprising vigor in gravel and even in dense grass. Its hardiness probably comes from its woolly leaves that retain moisture when needed and its long taproot capable of drawing water and minerals from deep down below. I had known Salvia verticillata well as a tough plant, having used it in less than ideal conditions without adverse results. Unlike other salvias, it does not need regular division or replacement, and indeed resents being moved (although recovery will happen within a year). Unsurprisingly vegetative propagation is difficult. Luckily, seeds are plentiful and easy to germinate, including the rare white form that comes true to type. For the rather special (but somewhat gloomy) all-dark cultivar ‘Purple Rain’ (which does not set seeds), basal cuttings in spring is the best option.

Fairly common in Slovakia too but only in short-grass meadows (including lawns) is Salvia pratensis. Linnaeus clearly observed the species’ habitat preference for pratensis means ‘of meadows’. Although Salvia pratensis comes in a variety of colors in gardens, the ones I saw flowering were all a particularly dark purple color. Flowering was not abundant in late summer because Salvia pratensis is a spring-blooming species. The few I saw flowering already had been mowed down and were on their second flush of flowers (an observation that I will not hesitate to put in practice). Although there was no color variation, the intensity of the color –the shade that my camera unfortunately refuses to capture as it should – impressed me. In the garden, Salvia pratensis does occur in various shades of white, pink, or purple, as well as bicolored. This species is usually propagated from seeds because clumps do not increase fast and therefore yield little divisions, but outstanding cultivars are occasionally propagated vegetatively from basal cuttings or tissue culture. One such example is the outstanding ‘Madeline’, a bicolor blue and white selection from the Dutch nurseryman and designer Piet Oudolf. Oudolf too has introduced a hybrid between Salvia nemorosa and S. pratensis (hybrids are now known as S. x sylvestris), ‘Dear Anja, in honor of his charming and eccentric wife. It is a luminous plant with blue flowers born out of dark magenta calyxes. If I were forced to choose only one salvia, ‘Dear Anja’ would probably be it. Unfortunately It is a difficult plant to propagate and has thus far remained rather elusive.

The last Salvia species I encountered on my walks in Slovakia less common and only in hedgerows and forest edges (sometimes even deep into the forest itself), was the lovely yellow Salvia glutinosa. I was surprised to see it in the shade since it has always grown well in full sunshine in my Canadian garden. Perhaps moisture is a deciding factor since Slovakia only gets half the rain we receive at home. Salvia glutinosa is a beautiful plant and one of my favorite salvias with its large heads of pale yellow flowers and its hastate foliage. It is the European answer to Japan’s Salvia koyamae, which coincidentally prefers partial shade. I look forward to trying Salvia glutinosa on the edge of our woodland, perhaps amongst Aconitum uncinatum or Actaea.

~Philippe Levesque and Eric

5-10-5: Laura Ekasetya, Horticulturist, Lurie Garden

Laura Ekasetya was a week-long guest horticulturist at Chanticleer earlier this year, and I sensed in her an astute and inquisitive mind about plants and gardens. It is infrequent that we hear about the individuals who maintain the work of creative visionaries while keeping it afresh and evolving, and Laura is one of those fortunate souls who oversees the Lurie Garden in Millennium Park, Chicago, Illinois with her team of coworkers and volunteers. Coincidentally her colleague Jennifer Davit, the garden’s Director and Head Horticulturist, was my classmate when I enrolled in the public garden management course at Cornell. She had nothing, but plaudits for Laura’s work in tending the garden.

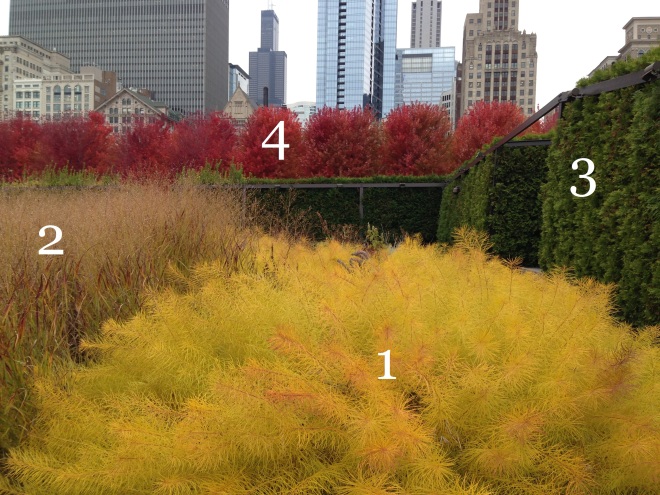

Anatomy of a Garden: Two Plantings at Lurie Garden

The principal genius of the Lurie Garden, conceived by Kathryn Gustafson, Shannon Nichol, Jennifer Guthrie (Gustafson Nichol Guthrie firm), and Piet Oudolf, lies in the ingenuity with which North American prairie plants are mixed with exotics to spectacular effect in an urban environment. A 15 ft tall hedge, a physical manifestation of Carl Sandburg’s “City of Big Shoulders’, gives muscular heft and the maple allees (Acer x freemanii [Autumn Blaze] = ‘Jeffersred’ keeps the scale proportional and intermediate between the skyscrapers and the perennial plantings. Because Chicago’s cold and snowy winters can truncate the winter interest of herbaceous plantings that Piet Oudolf is famous for, the structural stillness of the hedge and maple trees cannot be underestimated and by its virtue of solid mass, the former makes the garden’s loose naturalism more marked during the growing season, and the latter intercepting light at a higher level. Had not the Gustafson Nichol Guthire firm and Oudolf been perceptive to create this framework, the Lurie Garden overall looks lost against the domineering Chicago skyline. Below are two photographs of different plantings taken at different seasons.

One could say that the first photograph of the garden in autumn resembles abstract expressionism since colors – the scarlet ridge of maples, the angular contours of the hedge, the tawny seedheads of Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’, and the fine loose foliage of Amsonia hubrichtii – are sharply demarcated.

1. Amsonia hubrichtii

Restricted to the Ouachita mountains in Arkansas and Oklahoma, Amsonia hubrichtii commemorates the American conchologist (someone who studies molluscs) Leslie Hubricht who found it in 1942. Young plants resemble straggly pine seedlings, but will mature to form billows of fine-textured stems with 3 to 4 feet spread. Like other amsonias, Amsonia hubrichtii produces light cornflower blue flowers in spring. Although some garden writers have derided its widespread availability and potential overuse in landscapes, it still remains somewhat uncommon and should not be overlooked especially for its bright yellow autumn foliage. Full sun and regular soil will be satisfactory and a bit of self-seeding may be observed. The second photograph shows Amsonia hubrichtii in its spring attire (Number 6).

2. Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’

One of the earliest switchgrasses to be introduced to the trade for its reddish foliage, ‘Shenandoah’ is a German selection by Hans Simon who evaluated more than several hundred seedlings of ‘Hanse Herms’. Leaves emerge green in early summer and develop reddish tints in midsummer. ‘Shenandoah’ does not flop and remains remarkably upright throughout the season. The downsides is that the foliage seems more susceptible to rust than the green or blue-leafed cultivars and the roots, aromatic when dug, are irresistible to rodents, especially voles.

3. Thujas (Thuja occidentalis ‘Brabant’, T. occidentalis ‘Nigra’, T. occidentalis ‘Pyramidalis’, and T. occidentalis ‘Wintergreen’, Thuja ‘Spring Grove’)

Different Thuja cultivars fill out the hedging that surrounded the perimeter of the Lurie Garden and diminishes the unsightly effect of winter damage were one variety used. In a heavily trafficked urban environment, the thujas do not suffer from deer depredation and remain evergreen.

4. Acer x freemanii [Autumn Blaze] = ‘Jeffersred’

Freeman maples are hybrids between Acer rubrum and A. saccharinum that combine the best attributes of their parents. The form and brilliant scarlet foliage is inherited from Acer rubrum, with rapid growth and urban adaptability from A. saccharinum. In Manual of Landscape Plants (2009), Michael Dirr noted that Autumn Blaze has ‘rich green leaves with excellent orange-red fall color that persists later than many cultivars, dense oval-rounded head with ascending branch structure and central leader, rapid growth and Zone 5 hardiness, may be more drought tolerant than true Acer rubrum cultivars.” Indeed the scarlet color is a worthy ornamental characteristic of Autumn Blaze. Dirr does express caution over the overuse of Autumn Blaze in commercial landscapes.

By contrast, the second photograph taken in early summer depicts the Lurie Garden painterly in the Impressionist manner – the drifted plantings orient in unusual angles, the colors appearing brushstroke-like, and plants an essence of their selves. Not surprisingly, the Lurie Garden Design Narrative describes this section “bold, warm, dry and bright” and the its topography “a contoured, controlled plane experienced by walking on its surface.” Early summer is a bounteous time for herbaceous perennials which respond well to longer day lengths and consistent warmth.

1. Monarda bradburiana

Monarda cultivars from Europe have largely overshadowed the native species from which they were hybridized, and it’s a shame since the species seem to exhibit better mildew resistance and adaptability. Native to open dry woodlands in Southeast US and northwards to Iowa, the Eastern bee balm has attractive silver-green foliage and creamy pink tubular flowers. The calyces age attractively to a wine hue, an additional seasonal interest after the main floral display has finished. Here in the Lurie Garden, the wine calyces connect visually to the dark globes of Allium atropurpureum. Pollinators are usually drawn to its nectar-rich flowers, giving a strong case to cultivate Monarda bradburiana.

2. Allium atropurpureum

I first saw this allium at Nori and Sandra Pope’s late Hadspen Garden, Somerset, UK where the dark purple florets echoed the purplish-suffused blue foliage of Rosa glauca in the plum border. Used alone, Allium atropurpureum looks lost, receding in the background. However, its dark tone is a good chromatic foil for the purple Salvia river and Baptisia ‘Purple Smoke’. Some accounts have noted the short lifespan of Allium atropurpureum although excellent drainage may be the difference between success and failure. Topping up the bulbs annually will offset any gaps and maintain the display overall.

3. Amsonia ‘Blue Ice’ and Papaver orientale ‘Scarlet O’Hara’

Of unknown parentage (one parent is certainly Amsonia tabermontana), Amsonia ‘Blue Ice’ originated in the stock beds of White Flower Farm several years ago. It is a superb garden plant for its all around good looks – the buds are a winsome dark blue, habit is tidy and manageable, leaves dark green and lustrous (turning yellow in autumn), and pests seldom trouble ‘Blue Ice’.

The bright splash of red orange from Papaver orientale ‘Scarlet O’Hara’ prevents the planting from looking sedate, polite for a lack of better term. In a mixed planting like the Lurie Garden, Oriental poppies can be tricky to integrate because they left gaping holes during summer dormancy and resent crowding when foliage returns in late summer and autumn. In addition, it is easy to plant in the empty spaces vacated by dormant Oriental poppies.

4. Amsonia tabermontana var. salicifolia

Taller (24-36″) than ‘Blue Ice’ (12-15″) and bearing lighter hued flowers, Amsonia tabermontana var. salicifolia was among the first amsonias to be cultivated and still remains a classic for the perennial border. The terminal clusters of light blue flowers appear in spring and become bean-like seed pods in late summer and autumn. Be mindful of its siting since transplanting established amsonias is not a feat for the weak-hearted as their taproots probe long and deep.

5. Baptisia ‘Purple Smoke’

Sometimes the best garden plants are happy accidents and ‘Purple Smoke’ was a chance seedling discovered by the late curator Rob Gardner in the trial beds of Baptisia minor and B. alba at the North Carolina Botanical Garden. Sultry smokiness essentially sums up the appealing trait of this hybrid – the stems emerge an inky gray color rare among herbaceous perennials, the flowers a soft violet the color of evening dusk, and the pea-like foliage unfazed by heat and humidity. Mature plants can reach 50″ tall. In this planting above, the soft violet flowers are a good transitional hue between the salvias and Allium atropurpureum. Young plants do not resemble much and require some time to reach their full potential.

6. Amsonia hubrichtii

Lumina

Dear Jimmy,

Your post on the Spanish artist Joaquín Sorolla had me contemplating about light. We should practice ‘luminism’ more in gardening. Light is perhaps the most misunderstood and poorly considered element in gardens. Only are the plants’ cultural requirements weighed does it become significant. While we may appreciate its effect in interior design and architecture, for some reason we fail to apply the same priority in gardens, concentrating instead on hardscaping and plants. Focusing on hardscaping and plants is like deciding what furniture and decor will be without thought to the wall color and floors. Yet it is light that noticeably alters the mood and atmosphere of the garden – the silhouettes of trees and shrubs, the long shadows cast onto the walls, and the reflections in water features. Sylvia Crowe once wrote: “There is always a delight in looking out on to the sunlight from within a dark wood, or from between the columns of an arcade, whether they be the pillars of an Italian pergola or the trunks of a lime walk, and there is the unfailing effect of light falling on some special spot from surrounding shade.”

Studying the various nuances of light has revised my approach towards combining plants. Just as theatrical lighting affects our attention on the stage performers, the right light can accentuate plants. Simply it seems sensible to design a planting through light. I recall Nori and Sandra Pope explain how they observed where the light fell at various times against the curvilinear kitchen garden wall at Hadspen, letting it dictate what colors decreed the garden. Their tonal plantings modulated from light to dark, proving again that light underpins color. The same principle pertained to Great Dixter, renowned for its virtuoso color combinations that either soothe or excite depending on the time of day. In the High Garden there, the intense colors of tender perennials and annuals were heightened in the evening light than they were in the morning.

To bring light into the garden is to embrace the luminous quality of grasses. What makes the gardens of contemporary garden designers like Piet Oudolf, Tom Stuart Smith, or Wolfgang Oehme, appealing is the interplay of light between grasses and herbaceous perennials – the buoyancy of the former enliven the perennial flowers, propping up their decaying seedheads later. A friend cleverly interplanted Sanguisorba officinalis (burnet) among Stipa gigantea where the first rays of sunlight hit the garden. The grass has the kinetic and translucent magnetism, a perfect foil for the opaque dark Sanguisorba in summer and autumn. It is a magnetism seen hundredfold in a field of Miscanthus sinensis I once waded through at Yangmingshan National Park, Taiwan. High above the urban smog of Taipei, the clear skies highlighted a shimmery silver sea of plumes, a memorable sight that linked landscapes to my light fixation in gardens.

Being serious about photography taught me about light as well. Garden and landscape photographers often register the light carefully for the best pictures. Doing so slows you down as you walk around and observe the garden from different angles, and then the garden’s personality becomes more apparent. It always dismayed me to visit a garden at midday for the resultant photographs were washed out. Soon I reluctantly started to wake up before dawn and venture out when people were still asleep. That reluctance disappeared into contentedness – the still mornings, unsullied by nothing but birdsong, promised moments of beautiful repose. Those moments induce a dream-like state, suspended between surrealism and reality, fertile for creativity.

My appreciation for gardens and landscapes went deeper beyond color and form. I paid heed to Crowe’s finer points of light in the garden – the long shadows cast by trees across the lawn, the shafts of light splintering the morning mist, the backlit beauty of a solitary flower heavy with dew. It is an experience immensely private and not immediately apparent during the process of gardening – sometimes we are deeply engrossed in the mundane tasks on hand, forgetting to look up.

When I was in Australia, I was startled by the country’s hard light – the textures and colors, the leaves of eucalyptus or the rocky formations, were clear-cut and reflective. The clarity of the Down Under light forced me to rethink my perceptions previously informed by the Northern Hemisphere. Landscapes became more sculptural, abstract, and wilder. Genteel places created by homesick Europeans paled in comparison with their surroundings – the demarcations between the domesticated and untamed were more sharply drawn than those blurred in Europe and parts of North America. The stronger light only compounded that difference.

Every detail seemingly asserts itself graphically in the Australian light – the orange lichen encrusted rocks, pockmarking the east coast of Tasmania and Victoria, are fully saturated, nowhere muted as they would be in the Northern Hemisphere. Clouds seem more alive – their fluffy contours indelibly etched against the antipodean skies. Using Northern Hemisphere plants in these areas would feel too contrived and futile – they would appear discordant in the grand landscapes. More than anything, light sets the style of the garden.

Only in the higher elevations did the light wane, receding with more luxuriant plant-life and cooler temperatures. The mists chilled us as they would have elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest, the Yorkshire Moors, or the Californian redwood forests. Here greens, grays, and muddy browns dominated, taking over the whites, oranges, and burnt sienna of the coastal areas.

Such ruminations on light can be turned on without going overseas. As I drive to and from work home, I watch how the light shifts into dawn and evening. The low-angled light in autumn is a profound difference from the high summer light, a more golden luminosity not seen in spring, and it is one advantage of residing in the Northeast U.S. In more northern latitudes, the light seems weaker, diminished by the geographical proximity to the Arctic Circle. You become habituated to the subtle changes in the same way plants begin to respond to longer day lengths.

Deciphering light in gardens is our capacity to envince the atmosphere of a natural place. We have the benefit that Sorolla and other Impressionist painters never had – we never need to reproduce the light. Sometimes the methodical aspects of gardening can leave us incapable of creating the feeling, the emotional limitations and longings that precisely characterize the beauty of creating a garden. ~ Eric

Dichotomy of a Modern Garden: Bury Court

It is rare to find a garden that is a product of two designers – especially one runs the risk of creating a bipolar identity. Bury Court represents the fulcrum of two designers whose styles seem superficially similar, but upon closer inspection are different.

It is considered the first British commission that the Dutch designer Piet Oudolf designed in 1997 after John Coke, the owner of Bury Court, sought someone to collaborate on the courtyard garden. With Marina Christopher, John Coke operated the now-closed specialist nursery Green Farm Plants, one of the first nurseries to sell herbaceous perennials and grasses popular in today’s contemporary gardens. Coke found a kindred soul in Oudolf who combined plantsmanship and design (it didn’t hurt that Oudolf and his wife Anja ran a successful nursery selling similar plants as Green Farm).

Oudolf countered the asymmetrical shape of the exposed courtyard with curving beds book-ended with mounds and swirls of topiary. He filled the beds with his typical controlled compositions of perennials and grasses that are the defining norm for this style. The low to medium heights of Molinia caerulea and Deschampsia caespitosa are exploited for stylized meadows mixed with Dianthus carthusianorum and Allium sphaerocephalon and Digitalis ferruginea. Copied much elsewhere, these meadows have been reinvented in Oudolf’s subsequent gardens. Only the gravel garden and the formal pool feels slightly awkward, but exist as vestiges of the site’s former nursery. If the garden seems humbling in the light of his later work, it is due to its domestic scale limiting the drifting style Oudolf normally applies to expansive spaces.

Like Oudolf, Christopher Bradley Hole favors the large-scale use of grasses and herbaceous perennials. In an interview with garden writer and designer Mary Keen, Bradley Hole admits a particular fondness for plants ‘invaluable in their ability to reproduce, in an abstract way, the unique forms and seasonal changes within a garden setting.’ It is where this similarity with Oudolf begins and ends. Whereas Oudolf strives for a rather effortless, but romantic feeling reminiscent of natural landscapes, Bradley Hole aims for a minimalist and abstract interpretation. His herbaceous plantings often are squared off by paths, paved or grassed, and blocks of boxwood, yew, and field maple reinforces their geometric patterns. He unabashedly mixes different grasses together than adhere to the conventional practice of block planting – Miscanthus, Molina, Hakonechloa, and Stipa gigantea. His love of grasses does not diminish his soft spot for British native trees, especially Acer campestre (field maple) for its flexibility as a specimen tree or hedge. The results come together in his signature look – a grid-like labyrinth of twenty beds flowing with herbacous perennials and grasses and cordoned off by hedges seen here at the Bury Court garden created in 2003. In its hearth lies a tall oak pavilion adjoining a black pool, and north of the garden is a weathered oak garage building anchored by a grand sweep of Calamagrotis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’.

Intimate and abstract are not symbiotic, but they curiously come together here. As you enter the pathways, you disappear from sight as the grasses and tall perennials engulf you, creating that experience of being in a meadow or forest. One can imagine how transcendent it can be when the grasses become a shimmering sea of silvery plumes in autumn. It is the same effect seen at another superb garden Le Jardin Plume, France.

Of the two gardens, the Oudolf garden, once novel and innovative, looks funnily dated (I remember being asked by a friend which of the two I liked better) as its look has become much emulated elsewhere in the UK and continental Europe. The diversity of herbaceous perennials and grasses has given it a semblance of the traditional herbaceous border. Oudolf’s current style has since evolved from that of Bury Court – the topiary here that too defined Hummelo no longer plays a seminal role as it did in his early work (the wing-like yew hedges emblematic of Hummelo no longer exists). Blocky plantings have become looser or to borrow the oft used planting vocabulary ‘intermingling’. Innovative or not, there is no denying the significance of Oudolf’s Bury Court garden as a pivotal example of his early work. On the other hand, the Bradley Hole garden feels more fresh, helped by its simplicity in the linear dimensions and more restricted plant spectrum. It is an outstanding example of how the ‘naturalistic’ look can be tailored to a modernist garden without compromising its ethos.

Related Links

Planting: A New Perspective (www.plinthetal.com)

Pettifers (www.plinthetal.com)

~Eric

3 Seasonal Servings of Grasses

The prevailing trend of massing grasses for optimal visual effect overshadows the powerful impact of grasses as solitary specimens that can bring light or movement to plantings. Above are three images that illustrate this impact and gardeners can apply it to small gardens.

Self-sown Shirley poppies pop forth from the backlit seedheads of Deschampsia cespitosa, a cool-season grass. Typically Deschampsia cespitosa is used for massing in gardens and the overall effect is admittedly stupendous (witness the large-scale plantings done by Piet Oudolf and Tom Stuart-Smith in their work). Here Sally Johannsohn uses this grass to inject height and catch the late afternoon to early evening light, and the viewer pauses enough to admire the scene and notice the stone steps on the right.

Pennisetum villosum, a warm-season grass from northeast Africa, will take the baton from the fading Crambe cordifolia in the background. This planting cleverly integrates tender and hardy perennials, a tactic that the late Pam Schwerdt and Sibylle Kreutzberger honed to extend the seasonal interest during their time at Sissinghurst Castle Garden and later at Condicote. As long as the days are warm and long, Pennisetum villosum and Plectranthus argentatus will carry the scene well together with the Sedum whose flowers will turn pink or dark red.

In the Autumn Border at Pettifers, the arching form of Miscanthus sinensis ‘Yakushima’ breaks the rigid squat orange flowers of Kniphofia rooperi and visually mediates the two composites, white Chrysanthemum uliginosum and red-orange Helenium ‘Sahin’s Early Flowerer’, and Euonymous planipes is aflame against the grass plumes. Gina Price never allows her garden to go out without a last hurrah, and the Autumn Border is Pettifers’ pièce de résistance.

~Eric

You must be logged in to post a comment.